On 6 August the Commerce Commission published its Statement of Preliminary Issues (SOPI) for Z Energy Limited’s application to acquire Chevron New Zealand. SOPIs are published for the vast majority of clearance applications and are intended to “outline the key competition issues [that the Commission] currently consider[s] to be important in deciding whether or not to grant clearance.” Z, originally Greenstone Energy before being re-branded, was formed in 2010 following its purchase of Shell’s NZ distribution and retail business.

Below we:

- set out the areas of overlap identified by the Commission

- explain the key issues that the Commission will be testing; and

- provide a brief summary and comparison of the “longest” applications over the last decade

The Commission is accepting submissions on the application until 21 August and is currently aiming to make a final decision on the application by 18 December 2015, but has noted that this date may change.

The registration of the application is interesting. The transaction was publicly announced on 2 June and the Commission confirmed that it had received a draft application, around a month before the final application was registered on 1 July. Formal clearance applications are generally filed and publicly available soon after deals become publicly known. A delay of this length is unusual.

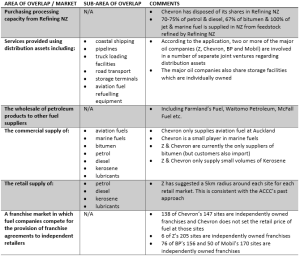

Overlap between Z and Chevron’s business

From its review of the application the Commission has identified the following areas of actual or potential overlap between Z and Chevron:

Key issues for the Commission to test

The Commerce Act prohibits acquisitions of business assets or shares which have the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in a New Zealand market.

When considering whether a deal will result in a substantial lessening of competition in any relevant markets, the Commission will compare the likely future state of competition under the proposed deal (the factual) with the likely state of competition under likely scenarios without the proposed deal (the counterfactuals). The counterfactuals will not necessarily include the status quo.

The key questions that the Commission will be focusing on when assessing whether the deal is likely to be anticompetitive are:

- Would the merged Z/Chevron be able to raise prices or reduce quality by itself?

- Would the merged Z/Chevron be able to coordinate with rivals to raise prices?

- Would the merged Z/Chevron be able to raise its rivals’ costs?

The first two questions are cornerstones for any merger analysis. That is, would the deal result in the merged Z/Chevron having sufficient market power that it could unilaterally raise prices or reduce quality, or would the deal result in an enhanced ability for the remaining players to explicitly or tacitly raise prices? The third question arises given the various joint ventures and collaborative arrangements that exist between two or more of the major players. Each of these questions is addressed in more detail in the sections below.

The Commission states that “[w]e are at this stage, generally concerned with the ability of the merged [Z/Chevron] to raise prices in the …markets outlined [in the table] above”. This view is unsurprising at such a preliminary stage, given the deal involves two of the major players in a concentrated and high profile industry.

After making market inquiries the Commission may provide the applicant with a Letter of Issues to highlight any concerns it has – giving the applicant an opportunity to address those issues. In complex cases where issues remain unresolved a subsequent Letter of Unresolved Issues may be provided, allowing the applicant a final opportunity to provide any further information or evidence to allay the Commission’s concerns. Unlike the SOPI, the Commission does not make these letters publicly available.

The applicant can at any time during the process offer to the Commission a structural divestment undertaking to address any competition concerns.

Could the merged Z/Chevron unilaterally raise prices?

To assess whether the merged Z/Chevron could raise prices the Commission has identified four issues for further consideration:

- How closely do Z and Chevron compete against one another? Businesses which compete closely are more likely to raise competition concerns than businesses that are not each other’s closest substitutes.

- What degree of constraint do rival suppliers provide? Would BP, Mobil and Gull (and fuel distributors supplied by those parties) constrain the merged Z/Chevron?

- Will the threat of entry and/or expansion constrain the merged Z/Chevron? How difficult is it for a new entrant to enter the market or for a current player to expand?

- Will customers have any countervailing buyer power? What options and incentives do customers have?

Would the transaction enhance the ability of the remaining players to collude?

To assess whether the transaction is likely to enhance the ability of the remaining players to either explicitly or tacitly collude the Commission will consider a number of factors set out in its Mergers and Acquisitions Guidelines (July 2013) including:

- Whether the characteristics of the product or service make coordination likely (eg markets for homogenous products, with static innovation and where there is repeated interaction between players are viewed as more susceptible to collusion).

- Whether the transaction will result in highly concentrated markets or eliminate a vigorous competitor.

- Whether the merged Z/Chevron and remaining players’ similarities (eg size, cost structure) offer enhanced incentives to coordinate.

- Whether the joint ventures and collaborative arrangements between the major fuel firms enhance the potential for coordination.

- Whether the threat of entry or the countervailing buying power of customers or suppliers would disrupt any attempts to coordinate.

The Commission notes though that it “will need to consider whether coordination is already occurring. If this is the case then we must assess the extent to which the merger would enhance this coordination.” This question goes to the heart of merger analysis. That is, what is changing as a result of the deal? If a market is already susceptible to collusion and a particular deal merely provides for the status quo, then the deal is unlikely to be viewed as “anticompetitive” (unless there is another buyer whose presence would materially reduce the ability to collude). Such a deal does not enhance the ability for the remaining players to collude and therefore changes nothing in that respect.

Would the merged Z/Chevron be able to raise its rivals’ costs?

As the major players are vertically integrated and have a number of joint ventures and other collaborative arrangements, the Commission will assess whether the merged Z/Chevron is likely to have an ability to raise its rivals’ cost at the expense of competition. According to the Commission, assets that the major companies “jointly own or operate (such as pipelines), as well as wholly owned assets (such as certain terminals)” could be used to raise rivals’ costs.

To assess whether the merged Z/Chevron is likely to raise rivals’ costs to the detriment of competition the Commission will consider:

- Whether the merged Z/Chevron has market power at one or more levels of the supply chain.

- Whether the merged Z/Chevron would have the incentive to worsen the input terms to its rivals (including refusing access) beyond any incentive to merely maximise profits.

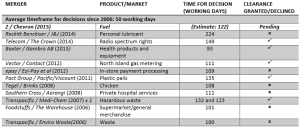

How long does the Commission take to assess an application?

Given the practicalities of investigating what often involves a number of complex markets and market participants, the Commission very rarely meets the statutory 10 working day timeframe for determining applications. Instead, the Commission’s usual practice is to seek one or more extensions with applicants, and generally aims for an average of 40 working days to make decisions. (Applicants invariably agree to extensions because if the Commission cannot otherwise reach a decision by the statutory deadline, the application is deemed declined.) However for various reasons, including the complexity of a particular merger, timeframes often exceed 40 working days.

The Commission’s initial extension to 18 December to allow a “6 month” timeframe for assessing the application, while uncommon, is arguably not surprising and should reduce the possibility of multiple extensions. However there remains a possibility that the Commission defers its final decision until 2016.

For reference to the current Z/Chevron application, the following table sets out some of the longer timeframes for mergers over the last decade: